Early

Days In Cleveland

My first contacts with the Company were in 1909. I

was Chief Clerk, Journal and Statistical Division, American Steel and Wire

Company in Cleveland. American Steel

and Wire was a constituent company of the United States Steel Corporation. I

made a trip to Pittsburgh to study the application of the Hollerith machines at

the Carnegie Steel Company. I decided that the machines could be useful at the

American Steel and Wire Company.

I ordered the machines through Phillip P. Merrill,

who was a combination salesman and repairman at the Tabulating Machine Company.

Merrill was in charge of the lakeshore installation of the New York Central

Railroad.

As I recall, ours was the only installation in

Cleveland at this time. After considerable delay, the machines arrived in the

summer of 1910. When the crates arrived, Mr. Merrill was notified. He connected the machines up to an

electrical current, came over to my desk and shook hands. Before he could get

out of the office I asked him what help might be given in regard to starting

the work. He replied that he was only required to connect the machine to a

suitable source of electrical energy. He assumed no further responsibility,

except to repair the machine, if it got out of order. That was the established

policy of the company at that time. This, by way of contrast to the Company's

current policy of assistance and help to customers. However, the machines were

successfully installed and proved to be a more efficient way of handling the

statistical and accounting work.

Two years later, at the solicitation of Mr. Merrill,

I entered the employment of the Tabulating Machine Company as a salesman.

Shortly thereafter, I offered a suggestion regarding a back-stop on the

punching machine. Information received from head office in Washington however,

was to the effect that this young man "should confine himself to selling,

not inventing, with the customary sarcastic reference that the idea was as

"useful as a button on a shirt-tail."

At about the time I joined the Company in 1912, a

decision had been made to divide the United States into districts. District

Managers were appointed in Philadelphia (T.J. Wilson), New York (Hyde), Boston

(Sayles), Cleveland (Merrill), Chicago

(Hayes) and Denver (Stoddart). The District Managers attended the annual

meetings, either in Washington or New York. Information regarding the

activities at the conferences was not divulged to salesmen. At that time it was

a small, but close Corporation!

The first convention of the Tabulating Machine

Company Division was held at the Vanderbilt Hotel in New York in December of

1915. Much to the surprise of the District Managers, and even more so to the

salesmen, a telegram was received from Mr. Watson notifying District Managers

that they were to bring the salesmen to New York to the annual convention. This

was the first mark of progress in the Company's affairs, since my connection

with it. This action brought the salesmen together as a team for the first

time. Mr. Watson will never realize the

uplift and inspiration that he imparted

to the salesmen of that day as a result of his conduct at the meetings. (Some

District Managers, however, were a

little confused!)

[back

to Contents]

Prospecting

For Customers

Embarrassing incidents occurred from time to time

while prospecting customers in the Cleveland area. One such incident was to have the General Manager or the

President of a company reach into his desk during a sales call and pull out a

four or five line letter from Dr. Hollerith.

The letter would say something to the effect that "In answer to

your letter of today, relative to the use of our tabulating machines for your

business. I can say only that your company's scope and activity is not

sufficiently large enough to warrant an installation of our machines."

This usually proved a hard one to hurdle!

The remarkable growth of the Company following the

radical departure from the non-lister to the printer justified the time, effort

and expense which Mr. Watson incurred in making this change. Mr. Watson

engineered this change in spite of the hostile and sarcastic criticism of Dr.

Hollerith who was opposed to a printing

tabulator.

Herman Hollerith

Herman Hollerith

The thought that the non-lister was superior to the

printer was so ingrained into the minds of the salesmen that it took quite a

period of time before the printer's obvious superiority was acknowledged. The

printer made complete reports without transcription, which was not the case with

the non-lister. Thus, hand printing and transcribing was eliminated. The

printer then became an integral part of the accounting system, rather than a

machine to grind out statistics.

In 1914, the Vacuum Oil Company of Rochester New

York, one of the Standard subsidiaries, discontinued its contract with us. The

reasons for this discontinuance was that the salesman who took the order had

designed a faulty product code. After the monthly sorting of the cards, the

product groups would have to be re-arranged by hand before tabulating. The

Company found that the work involved was greater than if they had just posted

the information by hand in the first place. Not surprisingly, the machines were

thrown out.

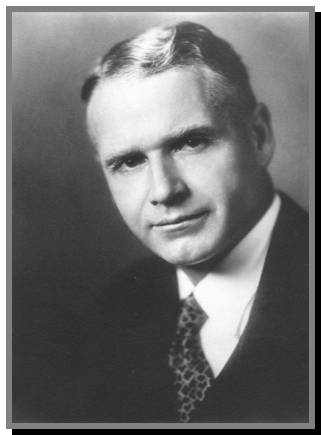

Walter Dickson

Jones ca. 1920

I had been working on Standard Oil Company of Ohio

and had almost got an order when news came of Vacuum's discontinuance. I found

out the facts about the faulty Vacuum code and then went to see the President

of Standard Oil, Mr. Coombs. I explained the situation to him and he agreed

that I could work with the Company Controller, Mr. Connelly, to determine a

more logical product code arrangement. I worked with Connelly for three solid

weeks and coded every one of their products in the natural and proper

arrangement. I got the order and installed the machines. Thereafter, Connelly

was considered the product coding authority amongst the various Standard Oil

companies.

One of the toughest pieces of prospecting that I

encountered had to do with a steel company in Youngstown, Ohio. After having

called numerous times and been turned down by a number of top officials, I

finally got a response from the Assistant-Treasurer. He set a time for a

meeting when we would discuss my proposition. Imagine my surprise when I

arrived at his office for the meeting and discovered that the sales

representative for our chief competitor was also on hand for the same meeting.

Mr. X, the Assistant Treasurer, said "Now, I have called you men in to

give both of you a chance to explain what your respective machines can do for

me. Now Mr. Jones, you tell us what your tabulating machine will do. When you

finish your story, then Mr. Doe will explain his proposition. I will then

decide which is the better of the two proposals. This sales call was made at a

time when the Company's stock was pretty active on the market and he telephoned

to one of his officials to see if they had the latest quotation. Apparently the

stockbroker's offices were pretty busy and he couldn't get the information.

After he had asked me to start my talk I got up and said that we could not get

anywhere with two salesmen wrangling over the respective merits of their

machine, and that I was willing to let my competitor have his say first.

I took the elevator to the ground floor, just at the

time when the 3 o'clock edition of the paper was being brought in. I quickly

got one of the paperboys, gave him a quarter and told him to take a paper up to

Mr. X right away and to tell him that Mr. Jones had sent it up to him. After

about an hour, I was invited into Mr. X's office. Mr. X was very cordial indeed

and thanked me for the newspaper. This little incident paved the way for very

cordial relations with Mr. X. I finally

had the satisfaction of taking his order.

[back

to Contents]

Commissions

- A Big Step

In 1912, a very limited and small commission plan

was introduced to supplement the salesmens' earnings. This scheme continued

until sometime in 1914. Speaking from a salesman's point of view in the

Cleveland district, I never knew the basis for the payment of the commissions. It did not concern me as most, if not all of

the commission went to the District Manager. It was discontinued because it was

not a well thought out plan.

[back

to Contents]

Hiring

Mr. Gershom Smith

It might be of interest to record how it came to

pass that the late Mr. Gershom Smith, comptroller of the Pennsylvania Steel

Company, Steelton, Pennsylvania, came to be appointed General Manager of the

Tabulating Division of the newly formed Computing-Tabulating-Recording

Corporation. Mr. Smith, while a good accountant and user of tabulating

machines, was quite unfitted by experience and training to head this division.

The facts as related to me by a friend to whom Dr. Hollerith had told the

incident, are as follows.

Charles R. Flint (the trust specialist who set up the

CTR in 1911)and

a Director visited Dr. Hollerith in Washington, to get his recommendations in

regard to someone to operate the Tabulating Division. It happened that a short

time before, Mr. Smith had presented Dr. Hollerith with a large framed

photograph of himself. In Dr. Hollerith's words, "As I raised my eyes to

Mr. Flint, they happened to rest on the photograph of Gershom Smith. I thought

to save myself a lot of bother, I might as well recommend him, for I fully

expect to buy this division back from CTR before my retainer expires. In the

meantime, Mr. Smith could not do much harm to the business, even if he could

not do much good, and I will be kept in touch with developments."

The young men (some of whom became District

Managers) whom Dr. Hollerith had trained in Washington to repair the machines

adopted his views. This was at a time when the Doctor was making his first

inroads with the railways and the insurance companies. The Doctor looked upon

and considered his customers to be clients, in a true professional sense,

rather than in a commercial sense. Hence, it was the rule to speak of customers

as clients. Another deeply rooted idea which came from Dr. Hollerith was that

the machines were to be used solely for statistical purposes, and they had no place

in the accounting field as such.

None of the young men who had been trained by Dr.

Hollerith had much, if any, accounting experience and it was therefore natural

that they did not see the sales opportunities for the machines in the

accounting field.

It was perhaps because of my background of

accounting experience and the fact that when I ordered the machines for the

American Steel and Wire Company, they were installed for accounting work

primarily. In that installation, the statistics were a by-product of the

accounting work.

In every order I took as a salesman in the Cleveland

District, I would always work in some accounting features. My theory was that

there was less chance of a discontinuance if the machines were part of the

company's accounting processes, rather than merely being used for the gathering

of statistics. I always insisted that the installation be under the control of

the company's accountant - this assured greater accuracy and it also

established friendly relations with the accounting department.

In the natural development of things, my

discontinuances were very few. In 1915 I took twelve new contracts and

installed them personally. There was not a discontinuance in my territory for

the whole year.

About twenty years ago (1924), Jim Bryce was

developing a high speed calculating machine, which was later put in the E.A.M.

line as the Multiplier. On account of

its speed and capacity, there were doubts raised as to whether such a machine

could be used commercially by existing customers. The sales Department was

consulted as to its potential. I was drawn into the discussion and asked for an

opinion. In conversation with Mr.

Bryce, Mr. Wilson and Mr. Lamotte, I pointed out that while there was little or

no work in the present installations that could support such a multiplier,

there were fields that we had not touched, where the multiplier would be

invaluable.

I cited the case of the municipal tax bill. The bill

must show the valuation of the property, which is calculated by three different

rates, i.e., school rate, municipal rate and the county rate. I estimated there

were between five hundred and three thousand cities in the United States who

could use a multiplier to advantage.

This angle interested Mr. Bryce, as well as the Sales Department with

the result that Mr. Lamotte asked me to write out my ideas about municipal tax

accounting. My ideas were turned over to the Research Department. The subject

of municipal accounting was one with which I was quite familiar, having worked

four years for the Town of Westmount, writing out by hand, and calculating, the

tax bills for the entire town.

In 1928, while having lunch at the Bankers Club in

New York with Mr. Mack Gordon, one of my old Cleveland customers, I was

discussing with him the marvel of being able to send Mr. Watson's photograph

through telegraph wires to Chicago.

Thomas Watson Sr.

Thomas Watson Sr.

[back

to Contents]

New

Ideas

The thought occurred to me that if a photograph

could be sent through space, it should also be possible to transfer a figure

from a document through a punching machine to a hole in a card and thus

eliminate the human error in punching.

In other words, the transferring of facts and

figures from the document of original entry would be done electrically, thus

completing the cycle of electric accounting. Upon my return from the Bankers

Club, I dropped into Mr. Watson's office and found him in conversation with the

late Andrew Jennings and explained my idea. Mr. Watson's comment was "If

it can be done, it will be worth a million dollars to the Company." I was

told to discuss it with Mr. Bryce. After talking it over with Mr. Bryce an

appropriation was issued for the experimental work to develop an electric eye

principle, which Mr. Bryce thought would be the best medium to experiment with.

[back

to Contents]

In

Europe

The Scale Company in France (a division of the

Dayton Testut Company) was sold because it was a losing venture. This was also

true of our experience with the German Scale Company. At the same time, there

was no better scale manufactured in France or Europe than the Dayton Testut

Scale.

However, the marketing and sale of the machines was

done through agents and salesmen in every corner of France. These salesmen

invariably operated without regard to Company policy, which resulted in

shortages and losses. The agents to whom the scales were shipped on consignment

were careless handlers of the Company's property, to say the least of it.

The late Mr. Jennings considered that the business

was profitable. This was so because, as he explained to me, what they lost in

agency operations, they more than made up for in the sales from the factory to

the agents. Shipments from the factory

to the agents were billed at full sales price and naturally showed a profit

over and above cost. I pointed out to Mr. Jennings that this was only a book

profit which only became a real profit when the agents paid in cash for the

machines that we had shipped to them. I also pointed out that the Company was

carrying the agents' accounts receivable which had not, and would not be paid because

all the agents were broke.

The arrangement with the Testut group in France

provided a clause that said that they agreed not to enter the computing scale

field and our Company agreed not to enter the non-computing scale field, both

light and heavy capacity. I subsequently found out that one of our strongest

competitors in the sale of computing scales in France and Italy was a company

financed and operated by the French Testup group. This constituted a breach of

their contract. At that time, the Dayton Tetsup Company was losing money, so I

came up with the proposition to sell the French group the Dayton Testup

Company, good will and patents, up to the point of sale, rather than enter suit

against them. Permission to negotiate was given by New York.

I approached Colonel Desrouche, a director of the

Dayton company, but not connected with the competitive scale company and gave

him to understand that an agreement might be reached. He in turn mentioned the

possibility to Mr. Testut and Colonel Montgomery, directors of the Dayton

Testut and principals in the competitive scale company. After two years of

thinking it over the French group stated that they were willing to purchase the

Dayton Testut.

On the date of consummation we had gathered in the

office of our attorney, Mr. Marion, and had agreed to the amount of stock that

we would take in the new Company and the cash consideration. There was only one

thing still up in the air; the verification of the count and quality of

machines in the hands of the agents scattered all over France. It had been

tentatively agreed that we would each appoint a representative who would make

visits to the various agencies and arrive at a valuation of each agent's stock.

In case of a dispute, a referee would be called in to arbitrate the difference.

The amount involved in the inventory of machines in the hands of the agents

amounted to about 3,250,000 francs.

Much to my surprise, Mr. Cadier, General Manager of

the Testup group made a proposition that if our group would consider a discount

of 600,000 francs, that they would settle in cash for the inventory, sight

unseen. In view of what I knew about the scale business in the United States

and Europe, and the irresponsible and careless way in which agents operated, I

considered this a good proposition from our point of view and accepted it.

Subsequent findings of the Testup group, when they checked on the agents'

inventories, proved that the inventory of scales when they finally got hold of

them showed a shrinkage greater than the 600,000 francs discount which was

agreed to.

The Tabulating Machine Company (TMC) was never

legally established as an operating company in France. It operated in the

offices of S.I.M.C., which was the French Company, at 29 Boulevard Malesherbes.

The work of rendering the bills to the customers

throughout all Europe, outside Germany, and the collecting of the amounts due,

was done by employees of the SIMC Company.

A fee was paid to SIMC for this work by the Tabulating Machine

Company. TMC maintained no bank account

in Paris or France. The payments for rentals by customers in Europe, outside of

Germany, were made out in US dollars, and sent to Paris. They were then sent by

registered mail to New York. The Company paid no taxes of any kind in France. I

was assured by the late Mr. Jennings that this arrangement was entirely legal.

One of the employees of SIMC, for reasons of

personal spite, denounced the TMC to the French Treasury Department in 1933.

The result was that two officers of the French Treasury Department appeared in

my office one day and demanded full information in regards to the operation of

the TMC, from the date of its inception.

As this looked to be serious business, I stalled the agents and made an

appointment with them for the following day. I went down to see Mr. Marion, our

solicitor, and reviewed the case with him. Mr. Marion stated that in his

opinion the French tax authorities had grounds to impose a tax, and its size

depended upon the nature of our defense. He offered his assistance, but I had

found from contact with him that he lacked force as a negotiator and besides,

his attitude showed that he had already prejudiced the case. I then got in

touch with New York and asked that Mr. M.G. Connaly be sent to Paris to assist

in the defense of the Company's interests.

In the meantime the agents, armed with the authority

of the French law, conducted a cursory investigation. During this preliminary

investigation I got as much information out of them as possible in order to get

a line on the scope of, and pertinent facts by which they hoped to prove their

case. When they presented their initial findings, they had arrived at a tax of

between 50 and 60 million francs. They were very decent however, and when I

explained that a representative from New York was coming over to go in to the

matter in greater detail with them, they agreed to hold off making an arbitrary

tax demand until the representative arrived. As a result of Mr. Connaly's very

proficient presentation of our case, together with whatever assistance I was

able to provide, the tax was reduced to about 2,300,000 francs. This sum

included all penalties.

[back

to Contents]

The Valtat Wrongful Dismissal Suit

When I arrived in Paris in

1930, I was told by Mr. Jennings of the Valtat suit.

Valtat was an EAM salesman who had been dismissed by

SIMC. He promptly brought suit against the French Company for unjust dismissal,

claiming two or three hundred thousand francs damages. Jennings then brought

suit against Valtat for one million francs on the grounds that he had perfected

his process of card printing on the Company's time and property and in

violation of his contractual agreement, he had failed to turn his invention

over to the Company.

Before the case was tried, I went with Mr. Delcour

to interview our attorney, a Mr. Garcier. Mr. Garcier explained to us that

while he had not actually read the files, he would do so an hour or so before

the court opened and, in his own words, "Soyez tranquille. I will win the

case. Valtat's lawyer is young and inexperienced and anyway, I know the judge

who will hear the case." His unjustified optimism was rudely upset

however, when the judge listening to the pleadings of the two attorneys did not

even send it to a jury. Instead, he rendered a fast decision in favour of Valtat,

costs and damages against us. Valtat had been illegally discharged and he had

not been paid the full indemnity allowed under French law.

M. Garcier immediately appealed the case and then

asked me for instructions. I consulted with Mr. Porter, an American solicitor

living in France. Mr. Porter advised us not to press the suit against Valtat, but to negotiate directly

with him.

Valtat seemed to be a fairly decent Frenchman. His

story, later confirmed, was to the effect that he had worked as a salesman for

SIMC. During that time he had had a good territory, sold more than any other

salesman and had made good commissions. He said that he had been quite

satisfied with his relationship with the Company. On a Monday morning he

received a letter signed by Mr. Delcour, telling him that his territory was

reduced and that his commission rate was reduced, effective the first of the

next month. He protested to Delcour and was fired.

I had several interviews with Valtat and finally

convinced him to withdraw his suit for a settlement of 50,000 francs. This left

him in a friendly mood for the negotiations that subsequently took place in New

York where the Company brought the rights to his punch card printing process in

all countries except France.

I am still convinced that

his process has merit.

Alone and with small capital he was able to devise a

process to stick two pieces of wrapping paper together, cut and print them and

call it a tabulating cad. His card worked and he sold them for less money than

our card and our competitor's card and still made money. It was free from

carbon specks and slime holes, did not warp and withstood humidity as well or

better than our cards.

[back

to Contents]

French

Government Graft

The following illustrates the mentality of a certain

type of French government official, and their attitude towards what is commonly

known as 'graft'.

One day in 1932 I received a phone call from Mr.

Lawrence, a salesman of SIMC, our French Company. He wanted me to authorize a

payment of 30,000 francs to a French government official. Lawrence told me that this payment would

secure an order for six complete installations in six different departments of

the French government. This one order

would provide us with an annual income of 30 million francs. Lawrence further

stated that once the order was signed, we would also be required to make a

one-time payment of 3 million francs - to be divided amongst the higher-ups. My

reply to Lawrence was "Not one centime!" Not surprisingly, the order

went to a competitor.

In due course, a million and a half dollars worth of

competitor's equipment arrived at LeHavre. It was unloaded and placed in a

warehouse. The French government refused to accept delivery. The equipment remained in storage for a couple

of years at which time our competitor tried to sell it throughout Europe for

half price.

Graft was very flagrant and open in the Balkan

countries - no doubt a hang-over from the days of Turkish domination. Graft was

even carried to the point where a Government official would give an order to a

company for goods which the Government had no intention of buying. The contract

would carry stiff penalties for contract cancellation. When the official

cancelled the order, the penalty would be paid by the government and divvied up

amongst the interested parties.

When I arrived in Paris, the late Mr. Jennings

explained to me that all tabulating machine price lists for the Balkan

countries were 10 per cent higher than

the rest of Europe. This 10 per cent

represented the amount of money that we would return to the 'interested

parties.' He even had a rubber stamp made up for Balkan price lists which said

simply "10% of prices added."

When I became European Manger, I countermanded these

instructions. I gave orders that EAM prices were to be the same in the Balkans

as in the rest of Europe and no orders to be accepted on which the Company was

required to pay anything other than the salesman's regular commission.

[back

to Contents]

The Block Brun Company - Warsaw

The Tabulating Machine Company agent in Poland was

the firm of Block Brun Company, appointed by the late Andrew Jennings in 1927

or 1928. The principals were highly respected and wealthy, third generations

Moscow Jews. The headquarters of the firm was still in Moscow. The Warsaw

branch was managed by Stefan Brun, one of the partners who looked after the EAM

business.

Mr. Jennings was quite frank in stating one

particularity about Block Brun. The firm were our agents for EAM equipment. At

the same time, they were the agents for typewriters and adding machines of a competing

company. This was rather disturbing news to me and I made an early trip to

Warsaw to see how they operated. My investigation convinced me that the two

agencies were run by separate organizations of Block Brun. I was also convinced that they were

honorable in every respect to their obligations to the two companies.

The following is an example of just how square they

were. I was acting as chairman of a

German banquet at the Hotel Adlon in 1933 when a messenger brought in a note

from Stefan Brun saying that he had to see me at once on urgent business.

I excused myself to Mr. Rottke. Mr. Brun told me

that while he was waiting in an anteroom of the competitor's office, he

overheard their managers and patent attorneys discussing their plans to bring a

patent suit against Dehomag. The facts were passed on to Heidinger and Rottke

and a quick investigation was made by Dehomag. After an interview was held

between Dehomag attorneys and the competitor's attorneys, the proposed suit was

shelved. Brun had nothing to gain from

this personally, but his actions portrayed his loyalty. It is to be hoped that

he and his family were able to get back to Moscow before the German holocaust.

[back

to Contents]

German Vindictiveness

The following illustrates

the vindictive streak in certain types of Germans.

Kaun, manager of the Sindelfingen Scale plant in

Germany had been very leniently treated by Mr. Watson. However, matters finally

came to a head and he was let go. Under German law, Kaun was entitled to a full

year's salary and undisputed right to continue living in the house he occupied

on the Company's property. When he vacated the house at the expiry of a year,

it was wrecked from attic to cellar. He used axes, saws and hammers to destroy

the plumbing, the fixtures, the wiring, the stairways - even the plaster on the

walls.

[back

to Contents]

Saving

Men - Saving Materials

The Company believes in the salvage of men and

materials. The following incident bears out the wisdom of this approach.

Ferrara, of Italian parents, was brought from

Brooklyn to Milan to strengthen the EAM division of the Italian Company.

Vuccino, Manager, assigned him to a territory in Milan. For some reason or

another, he did not do well. After four or five months, Vuccino wrote to me to

say that he was letting Ferraro go. I wired to him to hold off until my next

visit to Milan.

When I got to Milan a week or two later I found that

people in the Italian organization were hostile to Ferraro because he came from

the States. I arranged for him to be transferred to Genoa as a full time

salesman with a period of six months to show his mettle. In less than four

months he had secured a large contract from Standard Oil and was on his way. I

met him a few years ago in New York and he was still with the Company.

[back

to Contents]

The Company in Canada

The Canadian Tabulating Machine Company came into

being as follows. St. George Bond, a Canadian from Toronto who lived in

Philadelphia, obtained the Philadelphia franchise from Dr.. Hollerith prior to

1910. But in a year or so it went bust, to the tune of 15 or 20 thousand

dollars. As a gesture, and more or less out of sympathy, Dr. Hollerith gave

Bond a license to operate in Canada in 1910 and Bond then formed the Canadian

Company. The terms of the contract

called for a 20 per cent royalty payment on all rental revenues. The machines

wee to be supplied by Hollerith at cost and second hand machines were to be

shipped at nominal value. Larry Hubbard, who had received his training with

Hollerith in Washington was engaged to run the Company. The first order he took

was from Mr. Fletcher of the Library Bureau and the machine was installed in

Toronto in December of 1910.

Hubbard then set up an office in Montreal on St.

James Street. In 1911 he wrote one contract, in 1912 four, in 1913 three - all

of these are still users. By 1918 he had 41 customers with an annual rental of

about $60,000.

As I recall, prior to 1914 Canada was operated from

the United States as part of the territory of the Rochester agency of the ITR

Company of New York. From time to time, James, the Rochester manager, sent

salesman up to Canada to get business. The late Jack Barry perhaps spent more

time in Canada than any other IBM salesman. Mr. Barry later became Sales

Manager of the ITR division and when he died in 1929, had become the Sales Manager

for the entire Heavy Duty scale division. In 1914, when Mr. Mutton was placed

in charge of the ITR Company, the representation from Rochester was

discontinued and Mr. Mutton bought his time recorders directly from the parent

Company in Endicott. Later, when the Scale Company was also placed under Mr.

Mutton, it was recommended to Mr. Watson to get out of the plant on Royco and

Campbell Avenue and build a new one.

Mr. Mutton presented a plan to Mr. Watson of adding another story to the

plant. Mr. Watson accepted Mr. Mutton's

advice and it was only after a period of 20 years or so that the present plant

began to outgrow its usefulness.

In 1915 and 1916, and even before, competition

between the dial recorder and the time recorder was tough and considered a

serious factor in Canada. The dial

recorder was a sturdy and satisfactory machine. I found this out in spades when

I tried to trade 50 of them out of the Angus Shops of the CPR for new machines

of ours. Some of them had been in use for over 35 years and were still going

strong. The dial recorders were manufactured by the W.A. Wood Company of

Montreal. Mr. Mooser, later factory manager in Toronto built them. Mr. Mutton,

who was an astute and shrewd businessman, made strong recommendation to Mr.

Watson that the Company buy out the Wood Company factory and patents. This was

done in 1917.

During about five months of 1918, St. George Bond,

who has since died, acted as sales manager of the Tabulating Machine Division

under the late Mr. Frank Mutton. Mr. Mutton was appointed Vice President and

General Manager of the three divisions of the CTR Company of Canada and the ITR

in the summer of 1918. It was then called the Computing Tabulating and

Recording Company Limited of Canada, a name later changed to International

Business Machines Co. Limited.

To go back a year or so, by December of 1917 the

Tabulating Machine Company of Canada was unable to meet its payments for the

purchase of machines. While Mr. Watson had given Mr. Bond ample time to arrange

his finances to meet his obligations, he was unable to do so and some form of

relief had to be sought.

Mr. Watson then engineered the plan of forming a

Stock Company in Canada. This company would acquire majority rights in St. George Bond's interests in the Tabulating

Machine Company of Canada and the Davidson rights in the Computing Scale

Company of Canada for cash/stock in a new company. This was done in the summer

of 1918. During these meetings, several

amusing incidents occurred. Once, in the middle of the lawyers wrangling about

values and amounts claimed by interested parties, Mr. Mutton demanded that the

people representing the New York interests, Mr. Rogers and Mr. Houston, meet

with him outside the room on a matter of great importance. Rogers and Houston found

Mr. Mutton at the end of the corridor, seated on a radiator with his legs

crossed. His important question involved the advisability of having his name

placed on the letterhead as the General Manager of the new Company.

In 1926 and 1927, all of the stock owned by the

public was bought up by the corporation. Rogers and St. George Bond were the

agents acting on behalf of the corporation in this transaction. Since that

date, the Canadian Company as been 100 per cent owned by the International

Business Machines Corporation of New York.

Between 1935 and 1939 the income and profits of the

Canadian Company increased 70 per cent. From 1935 to 1943 the income and

profits increased 800 per cent. While it is true that this remarkable growth

has taken place during the war years, it should not be overlooked that the

extreme confidence, both on the part of business and the Government in Ottawa,

led them to place their orders with our Company.

This confidence was based upon the performance of

the machines, as well as the character and ability of the personnel in the

Canadian organization. These people, through lean years and good years have

worked conscientiously in the building of the good name of IBM in the minds of

customers and prospects. It may also be

said that the Government, in searching for the mechanical means to fill its

needs during the war for accounting and statistical requirements has, with one

exception, considered only our Company as a source of supply.

The prestige of the Company was greatly increased by

Mr. Watson's visits to Canada prior to and following 1937. In 1937, as each

year thereafter he met the most prominent men in Canada, commercial,

educational and governmental. He also made many public addresses. On September

2nd of 1941 he took the entire executive staff of the IBM Corporation to the

Canadian National Exhibition. The Company was being honoured at the CNE's

International Day. That evening Lily Pons and Lawrence Tibbett gave a concert

at the Band Shell in front of some 60,000 people. This large audience was addressed by Mr. Watson, Mrs. August

Belmont and myself. At that concert, a generous donation of $10,000 went from the Company to the Canadian Red

Cross to help in the war effort. While this large sum was given without

publicity, the kind comments of the officer and directors of the Red Cross

would have been heart warming to any IBM executives, could they have heard

them.

During Mr. Watson's visits many changes were made to

the form and conduct of the business. In the latter part of 1937 he purchased

the property on King Street. The executive offices were separated from the

factory and IBM executives could be at the heart of the city's financial

district.

In the very early days, there were only three

employees of the Company, all located in an office at 15 Alice Street. I

believe that Alice Street became Teraulay Street and the original site is now a

parking lot. In December of 1938 Mr. Watson purchased the Beaver Hall property

and the office building erected on this site is considered to be the most

modern of its kind in Canada. Having one of the Company's executives living in

Ottawa where he could mix it up with the various government departments and

personnel from 1935 onwards also helped the Company build up its business in Canada.

Another factor which had a lot to do with the

welding of the Company personnel into a

united team was Mr. Watson's authorization for the purchase of a country club.

This property, purchased in 1942, consists of 100 acres just outside the city

limits. It's fully equipped and has a play house and playgrounds so that the

entire family can enjoy themselves. Mr. Watson authorized the purchase of an

additional 100 acres adjacent to the Country Club. This property crosses the

main feeder line for the CNR and will make a suitable site for a manufacturing

plant as and when needed in the future. It is cheap land at the price and is

currently being farmed by the farmer who sold it to us, on an annual rental

basis.

[back

to Contents]

The

Story of the British War Orphans

Following the German invasion of France in May and

June of 1940, when England was in great danger, Mr. Watson, with characteristic

thoughtfulness for others, cabled

Stafford Howard, Managing Director of the ITR in London, inviting the

wives and children of employees to take refuge in Canada at the Company's

expense.

In response, nine mothers and nineteen children

arrived in Toronto on July 5th 1940. This first group was followed by a second group of three mothers

and four children on October 9th of the same year. They were

temporarily housed at the Sisters of St. John the Devine hostel at 49 Brunswick

Street in Toronto.

Mr. Watson then authorized the purchase of lake

frontage at Bronte, about 28 miles west of Toronto. This property consisted of

eight acres, including fruit and market garden and two fine houses. When Mr.

Watson and Mr. Nichol visited Toronto on July 15th, 1940 to inspect

the property, and make the necessary arrangements, certain reservations on the

part of some of the evacuees caused him to abandon his plan - and the property

was sold without loss.

The evacuees were the lodged in boarding houses in

the west end of Toronto and suitable arrangements were made for schooling etc. Now that return permits

are being granted by the British government, some of our families have returned

home and there will no doubt be others in the near future.

The policy inaugurated by Mr. Watson to encourage

employees to mix in community affairs and join business and trade associations

has had much to do with establishing the prestige and reputation of our Company, as well as the development of

the individual. The Company's employees represent a standard of intelligence

and character which fits them all for such a roll. The very nature of the

business permits and demands constant development along business lines. This is

characteristic of the successful IBM man and stamps him with qualities of

leadership, both in public speaking and leadership. He attracts attention

wherever businessmen gather.

In the United States and Canada you will find IBM

men in the forefront of sales executives' clubs chambers of commerce,

manufacturers associations and boards of trade. Honours and preferments seem to

come to them naturally. This is the natural product of the educational system fostered

and promoted by Mr. Watson. The Company is no place for the bounder or the

philanderer. We have had some in the business, but they don't stick.

[back

to Contents]

The

Company in 1914

At the time when Mr. Watson took over the management

of the CTR Company in 1914, it is safe to say that every member of the sales

force of the CTR thought that the Company was on the upswing of an unending

period of growth, and the equipment consisting of the No. 15 Key Punch, hard

punch, vertical sorter and the non-automatic, non-lister tabulator would do the

trick.

As a matter of fact, the initial impetus given the

business when Dr. Hollerith installed the large machines with the Railway and

Insurance companies, was petering out and the Company was running into shallow

waters. The progress made in the book

keeping, adding and listing machines, and the improvements made by a competitor

with a similar machine, was bidding fair to eliminate us as a serious

competitor in the office specialty field.

The Company was going down hill instead of up and if

it had not been for the new machines which the Engineering and research

Departments had developed under Mr. Watson, the Company would have been limited

to certain kinds of statistical work. These new machines such as the Horizontal

high speed sorter, Printing Tabulator with Automatic Group Control, Electric

Key Punches and many other devices, have made possible the growth of the

Company.

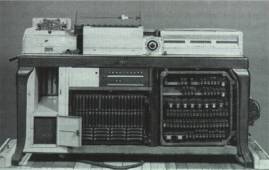

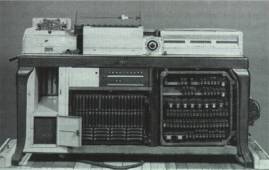

An early

combined tabulator/sorter

Concurrently with the improved machines, the sales

department was increased. All salesmen participated in a comprehensive

educational system on our products. A refresher course for the older salesmen

was also developed.

The Company had a new birth and was ready for larger

service to the business world, beyond the dreams of the original founders of

the Company.

[back

to Contents]

The

Story of Tauschek in Europe

The advent of Tauschek into the electrical

accounting field makes interesting reading.

Tauschek, a young Austrian living in Vienna, was a

clerk in a bank in Vienna in 1926 or 1927 or perhaps earlier. One of the

clients of the bank was the Powers Accounting Company. One of Tauschek's duties

at the bank was to scrutinize cheques, including those from the Powers

Accounting Company. In the case of the Powers Company, two signatures were

required.

On one occasion, Tauschek failed to note that only

signature was on a cheque destined for New York. The cheque came back and Tauschek took it over to the Power's

office to have it signed. Tauschek had never seen Power's accounting machines and

he asked the company manager explain to the machines to him.

Tauschek made

one or two visits to get additional information, and in the course of

conversation, he found that the mechanical tabulating machines were being sold

in Europe for between $15,000 - $20,000. Tauschek decided that the price was

too high and that a cheaper machine could be built which would do the same

work.

He then got in touch with patent offices in Germany,

Great Britain and the United States. Tauschek had copies of all patents which

had been issued concerning tabulating machines sent to him. He then took a

course in English so that he could read and comprehend all the material.

As a result of investigations, research and model

building, he secured patents from German, Great Britain and the United States

in and around existing patents. He then manufactured a model key punching

machine, a sorter and a tabulating machine, the principles of which were

slightly different from the existing types.

With this beginning, Tauschek entered into a

contract with the Rhein Metalls Company to develop his patents and build the

machines for commercial use. This contract was entered into around 1929.

Dehomag, our German subsidiary, was somewhat

disturbed by Tauschek as a potential competitor and was in favour of

negotiating with him.

During a trip to Europe in 1929, Mr. Watson had

Rottke (of Dehomag) and Tauschek come to London, to meet with himself, Mr. Jennings and myself (as

the newly appointed European General Manager).

The negotiations were held in Grosvenor House in London. After a week of

negotiating the IBM Company bought out

Tauschek's patents, and the models he had developed, with the exception of one

set of machines which Tauschek presented to the Vienna museum. As well, Tauschek secured five years of

employment with IBM, seven months of each year to be spent at the IBM labs in

the United States. As additional consideration, Tauschek also agreed to

unreservedly convey all his ideas and patents with regards to electric

accounting machines.

At about the time of the end of his contract with

IBM, it was discovered that he had proceeded with certain patents secretly

concerning the development of an electric eye principle. He had not turned this

work over to IBM, as per the terms of his agreement with us. Tauschek was

brought sharply to task by the Company but it began to look as if the only way

the Company could get redress would have been through the courts. In the midst

of negotiations, he fled, returning illegally to Germany. The rumour was that

he had been called back to Germany to complete work on a new type of machine

gun that he had developed for the German government.

[back

to Contents]

German

Capital Structure

There are a number of reasons which led up to the

increase of the capital structure and the consolidation of the three companies

in Germany: Dehomag, Ingemag (the scale company) and the Sindelfingen Scale

Factory. The capital of these companies

was nominal. I think that Dehomag's amounted to something like 300,000 marks.

We had kept the capital of the companies low on purpose, because the German

government taxed on capital stock. In fact, the two scale companies had never

shown a profit. Dehomag was different though and in 1932 and 1933 its profits

soared to four and five times its capitalization. The German Treasury began

careful scrutiny of firms such ours and of course this scrutiny was aided by

supplementary information provided by Nazi observers. The observers were

assigned by party leaders to all industrial plants throughout Germany. There

was always one observer keeping track of things and in some cases two or three,

depending on the size of the plant.

[back

to Contents]

Dancing

With the Devil - Nazis On Staff

At Dehomag we had a young Nazi by the name of

Fredericks who was on staff as an 'observer'.

I learned that Fredericks was one of the party of six Nazis who broke

into General Von Schleicher's residence during the infamous June, 1934 "Night of the Long Knives" purge

of Ernst Rohm and others.

General Von Schleicher

General Von Schleicher

Fredericks and the others executed Von Schleicher

and his wife in cold blood.

The fact that Dehomag was paying out annual

dividends many times the amount of its capital had resulted in certain

questions being asked by the German Treasury. At the same time, the Dehomag

Company had been made the target of abuse and criticism from the Nazi

controlled press throughout Germany on the grounds that the use of Dehomag

electric accounting machines threw clerks out of work. In government offices in

Hanover in 1932 civil service employees went on a bit of a rampage and

partially destroyed their newly installed Dehomag machines. This incident

received widespread publicity.

About this time our agent in Munich, a Mr.

Pappenburg had caused Rottke and Heidinger some concern due to reports coming

in to the Munich office concerning Pappenburg's unexplained absences from

work. They asked me if it would be all

right if they put a 'tail' on Pappenburg. As they seemed quite worried, I

agreed to their request. The reports we got back showed that Pappenburg was a

very active Nazi and that his absences were due to his attendance at various

conferences and meetings of the Nazi party. This gave Mr. Heidinger the idea of

using Pappenburg to meet Hitler at Hitler's Nazi headquarters. He wanted to

establish friendly relations with Hitler and the Nazi party so that the party

would discontinue its attacks on Dehomag. It is my understanding that Heidinger

became a Nazi party member at the meeting.

The result of this meeting relieved the Company from

further investigation by the German government and hostile criticism of the

Company by the Nazi controlled press stopped. In addition, the capitalization

of the German companies was increased to 7,000,000 marks. All the losses at the

Sindelfingen plant and at Ingomag were also capitalized. Over the next period of time, Dehomag and

the Sindelfingen plant became the only active units in Germany. The Small Scale

Factory (Ingomag) gradually folded. Interestingly, in 1934 the output of the

Sindelfingen plant was 85 per cent weaving machines - most of which were sold

to the Russian and German armies for the making of military uniforms.

Mr. Rottke did not become a Nazi until 1933. In the

fall of that year I called a meeting in Paris of all European managers which

Mr.Rottke attended. During the meeting Mr. Rottke took me to one side and said

that a demand had been served on him by the Nazi Party to become a member. He

wanted my advice and he showed me the letter and stamped self addressed

envelope that the Nazis had given him. He told me that he had been given 24

hours in which to answer their demands. From his manner, I surmised that he was

hoping that I would advise him not to join. But this was clearly a matter for

Rottke and his family to decide, on their own. I understand that he mailed his

application to join the Nazi Party the next morning.

[back

to Contents]

Bill

Collecting In New York

Collecting delinquent ITR and EAM accounts was a bit

different from collecting delinquent accounts in other businesses due to the

close and continuing relationship that existed between the Company and its

customers. Instead of pressure letters and calls from lawyers representing the

interests of head office, it was customary to have the EAM Manager or salesman

assume the role of bill collector when an account was past due.

This often placed our representatives in a difficult

position and frequent dunning calls to collect the money did not tend to

improve his standing with his customers.

Coming out of the twenties, there were a great

number of EAM customers who were delinquent. In addition, the accounts with the

government in Washington had become hopelessly in arrears for a number of

reasons, one of which was the failure of the billing department to put in

sufficient information to allow proper accounting to be made for the public

monies expended. Something had to be

done and it was decided to make a change.

The late W. C. Sieberg, who was the General

Bookkeeper of the EAM Division, was given the job. His first task was to

straighten out the Washington situation and then he was to move on and clean up

the rest of the accounts throughout the country. Mr. Sieberg spent about four months in Washington and got the

Government accounts up to date. At the same time that Mr. Sieberg was chasing

down delinquent customers, we brought

in Mr. Brown to do Sieberg's old job. Brown had been an accountant at a factory

and we brought him in so that he would gain a thorough knowledge of head office

accounting, which he could then take

back to the factory.

By way of commentary, it is my opinion that a good

EAM accountant, of broad commercial training, should always work as the liaison

man for the collection of delinquent accounts, rather than depending on the

salesman to do the collecting. The Company has ever, to my knowledge prosecuted

a customer for the non-payment of an account. Hence, it becomes a matter of how

and when to make a compromise agreement or settlement with a customer.

To an ingenious negotiator, it is almost always

possible to effect some form of agreement to protect the Company's interests,

and to ensure that the customer does not disregard his obligations to pay. In

certain cases, treasury stock or bonds have been accepted. I cite the case of a

Canadian aircraft company who was in arrears for over 18 months in 1936 and

1937. I interviewed the Treasurer of the company and we reached an agreement

whereby they would pay us monthly installation charges and the balance would be

held in suspense until they were able to make payments on the old balance. Any payments

made by the company were applied against the oldest balances. Within two and a

half years the account was brought up to date and it has not been delinquent

since.

[back

to Contents]

A

Historical Note on the Bull Company

It would seem proper to have some reference in the

historical data about the development of the Bull machine. The following is a

very sketchy outline and it should be supplemented by more accurate and

detailed information.

Dr. Fredrik Rosing Bull, a Norwegian, developed the

machines. When he died, he left his plans, his notes and diaries and the

machine's specifications

Dr. Bull

Dr. Bull

and whatever patents he had, to the University of

Oslo where they lay dormant for a number of years.

Emile

Genon, who later became our agent for Belgium, had been in the office specialty

business for years as a Belgian reseller of Elliott-Fisher and Underwood

calculators. In the course of his travels, he found out about Dr. Bull's

machines and that the University of Oslo had done nothing with them. Genon saw

possibilities. He got a group of interested investors together in Paris.

Members of this group included the auditor for the French Railway (a large

customer of ours) and general in the French army. Genon got enough money together to purchase all rights pertaining

to the Bull machines (except for Scandanavia) from the University of Oslo. As I

recall, Genon told me that he was able to buy these rights for $10,000.

The models were shipped to Paris, and under the

General's supervision, a limited number were built and installed in customer's

offices. According to all reports, they worked quite well. The Sorter was of the horizontal type and

was unusually light, in fact, about half the weight of our machine. The

Tabulator-Printer had a speed of about 230 cards per minute for listing and

adding. The type bar was of the rotary

principle. Under Genon's management, the Bull Company bid fair to make inroads

on the established business of the

Company.

At my suggestion, Dehomag sent two of their

representatives to investigate the machines. These representatives reported to

Heidinger and Rottke that the machines had considerable merit. The Bull

machines were demonstrated at the Paris Exposition in 1931 and attracted

considerable attention.

With this background, when Mr. Braitmayer visited

Europe in 1933, arrangements were made for him to meet with the Bull group in

Paris, and certain tentative negotiations were carried on in a regard to a

possible acquisition by our Company of the Bull Company

Genon

was later employed by our Company as our representative in Belgium. In November

of 1935 IBM Mr. Watson proposed to buy

all Bull assets for 2.8MF (including patents). In December of 1935 Emile Genon transferred 86% of Bull AG to IBM.

The next day, the Callies family proposed a new stock subscription of 6MF,

approved by Marcel Bassot, to avoid an IBM take over.

[back

to Contents]

Costs

and Profitability During the War

On March 2, 1943 the Canadian Company was asked by

the Department of Munitions and Supply to submit a statement of income, costs

and profit on any installations that might be considered war business with the

Department. This request was later broadened to include all government business

which could be classified as war business. The object of the inquiry was to

renegotiate our contracts with all government departments to establish fair and

reasonable profits on installations arising out of the war and to arrive at the

portion of the profit to be refunded.

At that time, the Canadian Company purchased EAM

equipment from the Parent Company on the basis of flat factory cost. We

therefore brought to the attention of Department officials that we were unable

to submit an accurate statement of costs. This flat factory cost did not

include administrative overhead, the costs of engineering, patents, development

or research. The Department indicated that it would be perfectly reasonable to

include any such items in our estimate of our costs and that the Department

wold have the right to scrutinize such items to determine whether they were

fair and reasonable.

On June 4, 1943 our Controller, A. L. Williams,

furnished a statement that showed the amount of such expenses, applicable to

the Canadian Company, expressed in terms of per cent, would approximate 5 per

cent of the total revenue of the Canadian Company for the year 1942.

The increase in cost of the over-all picture of the

Canadian Company, had the expense been included, would have amounted to

$167,687 (Gross Canadian income - $3,563,917) of which about $50,000 would be

the amount to be added to the cost of our war installations with the

Government. (Government installations in round figures, $1,000,000 per year or

approximately 25 per cent of total installations).

In view of the known losses we would sustain when

the war ended by discontinuances and cancellations, plus the unamortized value

of the machines which would be returned to us, I did not consider that the

figures being presented were fair for the Company. It was not enough for us

just to build up our cost figures.

I therefore decided to fight for the inclusion in

our costs of the 25 per cent royalty paid by other subsidiary companies. We were finally able to convince Department

officials to agree to the inclusion of this 25 per cent fee and an agreement

was reached by May of this year (1944).

On $1,000,000 of revenue, the royalty cost will amount to $250,000 as

against $50,000 had we decided to include IBM Corporation overhead as an item

of cost.

[back

to Contents]

Historical

Data - Census Machines

Perforated papers and cards were used to select and

control patterns in the weaving industry in the eighteenth century. This

principle was improved by Joseph-Marie Jacquard, a French inventor of Lyons

prior to 1806. The introduction of these 'Jacquard Looms' caused riots against

the replacement of people by machines.

Babbage

Babbage

It remained for Charles Babbage, an English

mechanic/mathematician to experiment with the principle of punched holes in

relation to a calculating machine. Babbage got government support for his

machine in 1822, but his 'Difference Machine' was never completed.

In the 1850's and 1860's, the development and use of

punched holes in paper for player pianos and organs was a great commercial

success.

It is perhaps with some of this background in mind

that Dr. Hollerith seriously considered adapting the principle of punch cards

for the compilation of the US census of 1860, from a chance remark made to him

by a young woman. He had been called to Washington in the early '80s to act as

a special agent in the Census Department. During a pleasure cruise on the

Potomac with Census Department co-workers, a young woman asked Hollerith:

"Why don't some of you men devise a card for the census work by punching

holes into it and making a machine do the rest of the work?"

By 1889 Dr. Hollerith had perfected and patented a

card with 12 rows of 20 positions for holes, to be punched on a Pantagraph

Keyboard Punch. His tabulator was similar to a printing press with the cards

being fed by hand and a handle which operated the press, thus allowing the pins

to press through the card. Wherever these pins went through the hole in the

card, electrical contact was made in a mercury cell below. The result was

registered in one of forty different counters. An attached sorting machine

consisted of a horizontal box with two rows of thirteen compartments, Each

compartment had a lid controlled by a magnet. This machine was controlled by

wires from the tabulator. To prepare for the next sort, the operator removed

the card from the tabulator and dropped the card into the compartment through

which the tabulator had just sent an impulse to cause the lid to open. The

compartment lid was then closed by the operator.

In April of 1889 a Commission was formed to advise

Mr. Porter, Superintendent of the US Census, as to the methods to adopt of

tabulating census data. To this Commission, three schemes were presented. Mr.

Hunt's scheme proposed to transfer the details given on the census enumerator's

schedules to cards, distinctions being made in part by the color of ink, and in

part by written notations, the results being reached afterwards by hand sorting

and counting. Mr. Pidgin proposed a scheme whereby chips would be used. These

chips could then be duly sorted and counted by hand. Mr. Herman Hollerith then

made his presentation, described above.

[back

to Contents]

Census

Slips and Chips

The three proposals were then put to the test in

four enumeration districts in St. Louis. It was found that the time occupied in

transcribing the enumerator's work (10,491 inhabitants) by the Hollerith method

was 72 hours and 27 minutes. The Hunt method took 144 hours and 25 minutes, Mr.

Pidgin's plan took 110 hours 56 minutes. He time occupied in tabulating was

found to be as follows:

·

Hollerith's

electrical counters - 5 hours 28 minutes

·

Hunt's

slips - 55 hours, 22 minutes

·

Pidgin's

chips - 44 hours, 41 minutes.

That settled it. Hollerith got the contact. The

Commission also estimated that based on America's population of 65,000,000, the

savings with the Hollerith machines wold amount to over $600,000. As a matter

for the record, that estimate was based on an average of 500 cards punched per

day, while 700 per day turned out to be the average - the savings were 40 per

cent more than expected. By way of

contrast, the work of tabulating the 1890 census was finished in ten months.

The previous census, undertaken in 1880, still was not fully tabulated when the

1890 census began. In fact, some of the data from the 1880 census was never

tabulated - this despite a workforce of

47,950 women tabulators working in the daytime and 32,935 men tabulators

working at night (figures from "Electrical Engineer", November 11,

1891 pp. 522).

Dr. Hollerith's connection with the U.S. Census

Department did not continue very much longer after the completion of the 1890

census. The relations were broken, as I understand it, through differences that

arose between himself and government officials or official. He withdrew and the

department started to build its own machines, incorporating the Hollerith

principles in the machines that they built. James Powers, a foreman in the

Census Department, developed a key punch which the Department adopted. Mr.

Powers, of Jewish origin, continued his developments and research work with the

result that he developed a horizontal sorter and printer-tabulator, both

mechanical, on which no patents had been taken out by Dr. Hollerith. Dr.

Hollerith had considered three methods for a power supply when he perfected his

machine; electrical, mechanical and compressed air. He took his patents out on

the electrical method - leaving others the option of developing machines with

compressed air or mechanical power.

This was the start of the Powers accounting machine.

Dr. Hollerith went on to assist in the census

processing for many countries around the world. The company he founded,

Hollerith Tabulating Company, eventually became one of the three that composed

the Calculating-Tabulating-Recording (C-T-R) company in 1914, and eventually

was renamed IBM in 1924.

[back

to Contents]

Thomas

Watson - A Model Employer?

New York, December 8, 1922

Mr. T.J. Watson

President

Computing Tabulating Recording Co.

New York.

Dear Mr. Watson:

I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for

the leave of absence granted me to bring my mother home from England and also

to express my regret that I was out after my passports when you wished to see

me.

My mother is upwards of 80 years of age and you can

imagine the joy it will be for her to have me to have me to look after her on

the homeward trip. I am looking forward

to the pleasure of seeing you on my return from England. I received Mr.

Braitmayer's message relative to seeing Mr. Stafford Steward of the I.T.R.

Company and will make a point of doing so when I am in London. Again thanking

you Mr. Watson, I am,

Sincerely yours,

Walter Jones

[back

to Contents]

Working

Through HR Issues in Paris

November 12, 1933

PERSONAL

Mr.

Walter Jones, European General Manager

Societe

Internationale de Machines Commerciales

29

Boulevard Malesherbes,

Paris,

France

Dear

Mr. Jones:

When

you first talked to me in Paris about Mr. Packard I was under the impression

that he had made a very serious mistake in his letter to Mr. Rottke requesting

certain information. Since my return, I find that Mr. Packard was simply

carrying out Mr. Nichol's instructions. Even if those instructions may be debatable

it is very unfair of us to criticize Mr. Packard for carrying them out, as we

was simply doing his duty.

I

could not help but sense a feeling that you and Mr. Packard were not

co-operating; because at the time I was under the impression that Mr. Packard

had made trouble with the German organization on his own initiative I did not

give the serious thought to his side of the case that I have since learning

that he was merely carrying out instructions.

Frankly

I worry about the lack of espirit de corps on the part of the organization in

Paris. It does not seem to measure up to Berlin or London. We sent Mr. Packard

to Europe to assist you at considerable sacrifice to the American organization,

and, of course, Mr.Packard made some personal sacrifice in moving a very young

baby, and then to find himself in an atmosphere, which I cannot help but feel

must worry him, it does not seem fair or in keeping with the IBM family spirit.

I

greatly admired Mr. Packard's attitude while I was there, especially when he

pleaded for an opportunity to go to Berlin and meet the men face to face who

had criticized him. As I observed the meetings in Berlin and in London it

seemed to me that Mr. Packard is well able to gain the friendship of all men.

It

is hard for me to write this letter, because what I am saying is based largely

upon what I sensed in connecting with the general atmosphere. Knowing that you

want to be fair at all times with your associates I am asking you to put

yourself in Mr. Packard's place and

review with yourself his experiences since his arrival in Europe and if you

feel that you have not been giving Mr. Packard the exact kind of treatment you

would expect, were you in his position, I will sure you will take him into your

confidence and put him in the right light in the eyes of all members of the

European organization, and get out of him his best efforts in assisting you to

do the big job which is before us.

With

kindest personal regards, I remain

Sincerely

yours,

Thomas

J. Watson, President

TJW:BW

Paris, December 5, 1933

Mr.

Thos. J. Watson, President

International

Business Machines Corp.

270

Broadway,

New

York City

Dear

Mr. Watson:

Thank

you very much for your letter of November 22nd which I have taken

seriously to heart.

It

has always been my desire to help and assist in the development of men in the

interest of the business and I will do everything in my power to cooperate with

Mr.Packard to this end. I have had this intention and desire since the moment

he landed in Europe.

He

has much in his favor. I find him keen and interested in every phase of the

business and anxious to accomplish the results that you count upon us to do.

You

are right. The Paris organization has not yet acquired the same espirit de

corps of Berlin or London. During my stay in Paris I have tried in every way to

improve it. Meetings, reunions at my house etc. have found it difficult to get the French organization to pull

together as a team. You can do a lot with them individually but our

organization in the past seemed incapable of the true IBM spirit.

M.

Virgile is bringing into the business men of a higher grade and when you see

the organization on your visit next year, I am confident you will see a big

improvement.

In

regard to the American representatives, we would be much better able to handle

the continental work if we were working together as a detached unit rather than

attached to the French organization. I believe as soon as it is possible to

establish a headquarters apart from them, after M. Virgile is able to handle

the responsibility, that there would be much better morale and better results.

Here

is nothing that I desire more than to weld continental Europe together in

accordance with the strong and sound organization lines laid down by you, and I

will work to this end to the limit of my ability.

Thanking

you sincerely for your letter,

I

remain,

Yours

very truly,

W.D.

Jones

Paris, December 1st, 1933

Dear

Mr. Watson:

I

sincerely regret having to advise you that after several weeks' silence Mr.

Jones simply notified me that I had to go and accept his proposal about taking

over a territory. It is a matter of great concern to me to see that several

younger men with much less service stay with the Company in executive positions

and I am sent away after almost 30 years. It is my firm belief that my services

and experience in the Paris office, if properly recognized and made use of,

would have been of some value to the business and I would willingly have made a

financial sacrifice to stay.

However,

I have no other alternative and must accept my definite removal from this

office to go out on the road and build up a sales organization at my own

expense. The twelve months salary awarded to me will have to serve for that

purpose.

With

the coming holidays in mind, I wish to thank you once again for the numerous

proofs of your kind interest in me and for the great kindliness you so often

and still recently showed me. I wish you and Mrs. Watson and your children a

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year and I hope that 1934 will bring health and

happiness to all of us.

Meanwhile

I beg to remain, with many respectful regards,

yours very sincerely, (unknown

signature)

[back

to Contents]

Walter

Dickson Jones (1878 - 1963)

Breconridge -

W.D. Jones' farm just north of Toronto. Early 1950's.

Walter Dickson Jones (born 1878) entered the employ

of the CTR Company in 1912 as a salesman of tabulating machines in Cleveland.

In 1917 he was made Assistant-Treasurer of the Tabulating Machine Company, the

Chief Subsidiary of the IBM Corporation. In February 1922 he was made manager

of the Cleveland office of the Tabulating Machine Company and was promoted in

1923 to be IBM Manager for the Eastern District, having charge of all

subsidiary companies - including the Tabulating Machine Company, The International

Time Recording Company and the Dayton Scale Company. Mr. Jones was made Assistant Comptroller of the IBM Company in

1924 and in 1927 became Treasurer and Comptroller as well as Director of the

corporation. In 1930 he was made Manager for Europe with headquarters in Paris

in which position he remained until 1934. In 1934 he assumed the Vice

Presidency of the Canadian organization of the IBM Company. In 1938 he was made

Chairman of the Board of Directors of IBM Canada. He passed away in 1963.

[back

to Contents]

Family

Photos - W.D. Jones

.

.

Rhoda, Muriel

and Francis Jones in 1916

W.D.'s bride. Rhoda

Wallace Haskell (1887 - 1960)

The Jones girls and their mother ca. 1937:

from left, Rhoda, Francis, Rhoda, Muriel and Catherine.

[back

to Contents]

MARCH ON WITH IBM

Verse:

The fame of IBM

Spreads across the seven seas,

Our standards fly aloft,

Proudly waving in the breeze,

With T.J. Watson guiding us

we lead throughout the world,

For peace and trade our

banners are unfurled - unfurled.

Chorus:

March on with IBM

We lead the way,

Onward we'll ever go,

In strong array;

Our thousands to the fore,

Nothing can stem,

Our march forevermore,

With IBM.

March on with IBM

Work hand in hand,

Stout hearted men go forth,

In every land;

Our flags on every shore,

We march with them,

On high forevermore,

For IBM.

[back

to Contents]

.

.